The full scope of this blog, declares the About tab above, is “anything to with Irish chess, from Labourdonnais-McDonnell to today”. Fair enough, you say, but how on earth could anyone say anything new about Labourdonnais-McDonnell? This was one of the most famous series of matches ever and has been exhaustively analyzed ever since.

For those not familiar with the topic, the Frenchman Louis Charles Mahé de Labourdonnais (b. La Réunion, 1797; d. London, 13th December 1840) was considered the strongest player in the world in his era. He played a number of matches in London against the strongest players of the day, culminating with a series of six matches from June to September 1834, totalling 85 games, against Alexander McDonnell (b. Belfast, 22nd May 1798; d. London, 14th September 1835). Though de Labourdonnais had the better of it, winning four of the matches to McDonnell’s one, with the last unfinished, the contestants were well matched and the standard of play very high for the era.

Here is a puzzling discrepancy, though. The second game of the first match, as given by the ICU on-line games archive, reached the position below after McDonnell’s 55. … g4:

The sequel, as given by the ICU collection, was 56. Bxg4 Ke7 57. Bc8 Kd6 58. Bxb7 Kc5 ½-½.

The sequel, as given by the ICU collection, was 56. Bxg4 Ke7 57. Bc8 Kd6 58. Bxb7 Kc5 ½-½.

But what is wrong with 56. … Nxg4 instead? After 57. Kxg4 Ke5 58. Kf3 Kf5 Black has the easiest of wins.

ChessBase.com’s “Big Database 2012” (5,000,000+ games) also gives the same continuation.

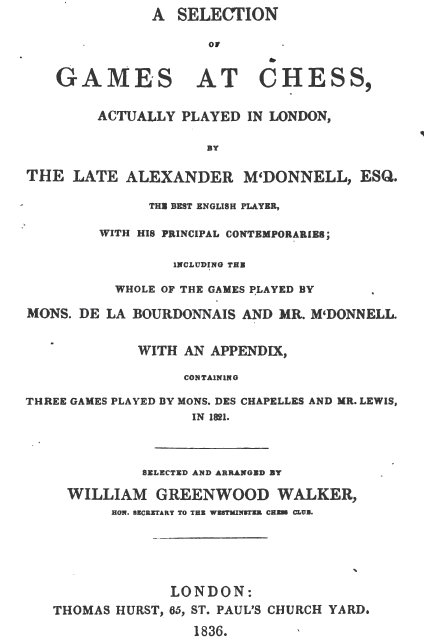

So did McDonnell fluff an easy chance? Actually, no: the databases are wrong, as they are so often for older games. The games from the match were widely published at the time, and since the books are long out of copyright we can access the originals on Google Books. The games were originally noted down by William Greenwood Walker, secretary of Westminster C.C., where the games were played, and he included them in an 1836 collection of McDonnell’s games:

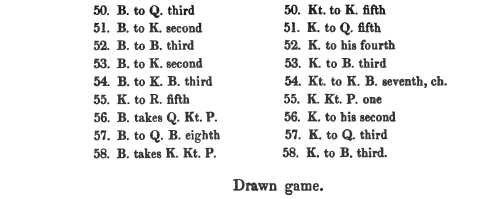

And here is the end of game 2 (p. 136):

That could hardly be clearer (apart from the ancient notation, that is): White captured the queen’s knight’s pawn first, and then after Bc8, the king’s knight’s pawn. This is also the version given by William Lewis, A Selection of Games at Chess (London: Simpkin and Marshall, 1835), p. 15 (adding some garbled moves at the end and calling it game 3), and by George Walker, Chess Studies (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1844), p. 1, both also available on Google Books.

So the actual finish was the much more reasonable 56. Bxb7 Ke7 57. Bc8 Kd6 58. Bxg4 Kc6 ½-½. (Click to replay the full game.)

This is also the version given in various modern books, e.g., Cary Utterberg’s De la Bourdonnais versus McDonnell, 1834: the eighty-five games of their six chess matches, with excerpts from additional games against other opponents (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2005), p. 51, citing Levy and O’Connell’s Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games (1981).

So an injustice to McDonnell is corrected. But where did the spurious version come from? It’s not just a matter of confusing the two knight’s pawns: in the spurious version Black can’t play 58. … Kc6 at the end, so someone “corrected” it to 58. … Kc5.